- Home

- Transplant Process

Transplant Process

Criteria for liver transplantation list

All citizens are eligible to access liver transplantation in Ireland. Citizens of other European Union countries (visiting or residing in Ireland), registered asylum seekers, and migrants with residency rights are also eligible. Any patient can be referred for a liver transplant assessment, and there are no overt administrative or financial barriers to referral. Patients are listed using standard international criteria. Because waiting times are still relatively short by international standards, there are no minimal Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) criteria for listing. The MELD is a calculated formula used to assign priority to most liver transplant candidates based upon their medical urgency and includes determinants such as liver functions blood tests, creatinine, INR (measure of blood coagulation time) and kidney dialysis requirements.

During the liver transplant assessment, a potential recipient will undergo pulmonary (lung) function tests, chest x-ray, blood tests, heart function tests, a CT (computed tomography scan) and an ultrasound.

Currently in Ireland, all donor livers are from deceased donors, while in many countries including Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Slovenia, living donor transplants are also undertaken.

The surgery

The liver transplant surgery is performed by a liver transplant surgeon or hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeon, and a surgical team including surgeons, anaesthetists, theatre nurses and others. The surgery – orthotopic liver transplantation – generally takes between five and eight hours to complete, during which time the potential recipient is under general anaesthetic. There are two main stages which include removal or the diseased liver (stage 1) and replacement with a healthy donor liver (stage 2).

Stage 1 Removal of the diseased liver An incision is made in the abdomen of the potential transplant recipient (an inverted ‘J’ shape known as the Makuuchi incision or a Mercedes Benz incision, shaped like the car badge). These incisions are both referred to as bilateral subcostal incision with midline extension and provide adequate exposure for surgeons to complete the required task of hepatectomy or native liver removal.

An incision is made in the abdomen of the potential transplant recipient (an inverted ‘J’ shape known as the Makuuchi incision or a Mercedes Benz incision, shaped like the car badge). These incisions are both referred to as bilateral subcostal incision with midline extension and provide adequate exposure for surgeons to complete the required task of hepatectomy or native liver removal.

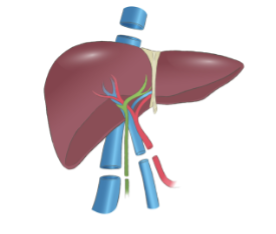

Actual removal of the diseased liver is by one of two methods: removing the inferior vena cava and replacing it with the vena cava of the donor liver or retaining the recipient’s inferior vena cava and connecting the donor liver to it. These methods are known as caval replacement (the classical procedure) and side-to-side cava-cavostomy (the piggy-back method) respectively. Either option is suitable but is dependent on the surgeon’s preference, and the best option for the individual recipient’s anatomy. During this stage the blood vessels in and out of the liver (hepatic artery and portal vein) and the bile duct are also cut (see diagram).

Stage 2 Replacement with healthy donor liver

The insertion of the healthy liver will be in the exact location that the diseased liver was removed from (orthotopic transplant). In a similar but opposite way, the liver is placed in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. The blood vessels (inferior vena cava, portal vein and hepatic artery) which were disconnected from the diseased liver are connected to the donor organ. Additionally, the gall bladder of the donor liver is removed, and the bile duct is connected to that of the recipients. Typically, before the incision is stitched and closed, two drains are inserted into the abdomen to collect excess fluids and blood which may flow from the abdomen for a number of days post-transplant.

During the surgery Removal and replacement of one’s liver is a complicated surgery and the patient’s subsequent recovery is paramount. As such, a number of measures are put in place to both protect the patient during the surgery but also to ensure that the recovery is as uncomplicated as possible. These include the insertion of an endotracheal tube into the windpipe and its attachment to a ventilator to assist breathing. A nasogastric tube is inserted into the nose to remove gas from the stomach. This tube may also be used as a feeding tube post-transplant.

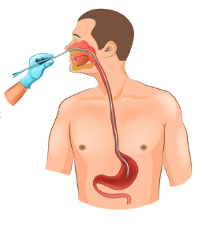

Removal and replacement of one’s liver is a complicated surgery and the patient’s subsequent recovery is paramount. As such, a number of measures are put in place to both protect the patient during the surgery but also to ensure that the recovery is as uncomplicated as possible. These include the insertion of an endotracheal tube into the windpipe and its attachment to a ventilator to assist breathing. A nasogastric tube is inserted into the nose to remove gas from the stomach. This tube may also be used as a feeding tube post-transplant.

Other tubes and catheters are inserted into the groin, neck and arms to both introduce medication and fluid, in addition to monitoring the patient’s condition.

A catheter is also passed into the bladder to drain urine until a recipient can use a toilet (see diagram).

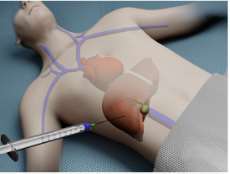

Most of these tubes and catheters are removed a few days post-transplant. A number of blood transfusions may be necessary both during and following a liver transplant. In addition, intraoperative cell salvage or a cell saver procedure (see diagram) describes the process of collecting a patient’s own blood lost during surgery, its cleaning and re-introduction back into the body. This is preferable to reduce the need for allogenic blood transfusions particularly when blood donations rates are low.

Most of these tubes and catheters are removed a few days post-transplant. A number of blood transfusions may be necessary both during and following a liver transplant. In addition, intraoperative cell salvage or a cell saver procedure (see diagram) describes the process of collecting a patient’s own blood lost during surgery, its cleaning and re-introduction back into the body. This is preferable to reduce the need for allogenic blood transfusions particularly when blood donations rates are low.

Ducts and dopplers!

Not long after your transplant – a day or two – you might be introduced to ‘ducts and dopplers’. This describes a non-invasive test using doppler ultrasonography – an ultrasound using the Doppler effect to measure the blood flow through your blood vessels, and bile flow in the bile duct. The Doppler effect is described as the change of sound frequency due to motion; when an ambulance with siren passes by you, it changes in sound frequency as it moves relative to where you are. Unlike a typical ultrasound, doppler ultrasound can detect and demonstrate blood flow. This is why it is undertaken in liver transplant recipients; it assesses the patency or condition of the hepatic artery, portal vein, hepatic veins and common bile duct in recipients.

Not long after your transplant – a day or two – you might be introduced to ‘ducts and dopplers’. This describes a non-invasive test using doppler ultrasonography – an ultrasound using the Doppler effect to measure the blood flow through your blood vessels, and bile flow in the bile duct. The Doppler effect is described as the change of sound frequency due to motion; when an ambulance with siren passes by you, it changes in sound frequency as it moves relative to where you are. Unlike a typical ultrasound, doppler ultrasound can detect and demonstrate blood flow. This is why it is undertaken in liver transplant recipients; it assesses the patency or condition of the hepatic artery, portal vein, hepatic veins and common bile duct in recipients.

Liver Biopsy

A liver biopsy may have been performed prior to your transplant as a diagnostic tool to make a diagnosis or to determine how well treatment for liver disease is working and to determine the severity and stage of liver disease. For example, a liver biopsy can diagnose Wilson’s disease, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis. A liver biopsy may also be performed following a transplant to monitor the health of your liver, to investigate graft rejection or if there are issues of concern for your medical team.

Simply, a sample of your liver is removed for analysis in a laboratory. This typically occurs by one of three methods: percutaneous biopsy, transjugular biopsy or laparoscopic biopsy, the former being the most common. A percutaneous biopsy involves the insertion of a needle into the right side of your abdomen under the ribcage and into your liver. As the needle passes in and out, you might be required to hold your breath. Prior to the procedure, you will receive a numbing agent at the incision area and will feel little pain. Following a liver biopsy, you may be required to lie on your right side for a 2 to 4 hours, to rest and recover. There will be some discomfort, but pain medicine should relieve this.

Simply, a sample of your liver is removed for analysis in a laboratory. This typically occurs by one of three methods: percutaneous biopsy, transjugular biopsy or laparoscopic biopsy, the former being the most common. A percutaneous biopsy involves the insertion of a needle into the right side of your abdomen under the ribcage and into your liver. As the needle passes in and out, you might be required to hold your breath. Prior to the procedure, you will receive a numbing agent at the incision area and will feel little pain. Following a liver biopsy, you may be required to lie on your right side for a 2 to 4 hours, to rest and recover. There will be some discomfort, but pain medicine should relieve this.

The two other biopsy options – transjugular and laparoscopic – may be performed if the percutaneous method is unsuitable. The transjugular biopsy refer to the insertion of a plastic tube into the jugular vein in your neck to access the hepatic vein. Use of contrast dye and the insertion of a needle follows and a sample is obtained from the liver. Both the tube and needle are subsequently removed. The small incision is dressed with a bandage.

A laparoscopic biopsy entails a general anaesthetic and a number of abdominal incisions. Because the patient is unconscious, this procedure allows a physician to be more explorative and for more than one sample to be removed. Following retrieval of the samples, the incision is closed, and you can recover.

The latter options may be considered if you have bleeding or blood-clotting issues, you have a tumour, you have trouble holding still during a procedure such as this, you have a liver infection or you are obese.